The want that makes me write is always caught between kinds of excess. One is easy to explain. It’s the desire always for more. For more attention. More sales. More fame. More glory. For each book to exceed the last. It’s a frustrating desire, because so often frustrated.

It’s a desire for a kind of luxury, for a displacement from ordinary life. In modern times luxury means something like comfort beyond necessity. I’m on the road, on book tour. In Venice the hotel is an ordinary one, and on the bed there are two pillows. In Rome, a luxury hotel, so on the bed there are six pillows. Luxury expresses itself through sensory details that communicate additional time and expense. In this kind of luxury, quantity expresses quality.

There’s an older sense of luxury as sensual, frivolous, sexy life. A life not devoted to the reproduction of more of itself. A life displaced towards difference rather than more of the same. A luxury you can’t quantify, can only feel. Sometimes I want that other luxury, in life, and in writing.

Writing itself can be a luxury, but what kind? Roland Barthes writes in The Pleasure of the Text: ‘does luxury language belong with excess wealth, wasteful expenditure, total loss? Does a great work of pleasure (Proust’s, for example) participate in the same economy as the pyramids of Egypt?’1 The commodity form recuperates writing. Its luxurious uselessness becomes a thing of market value. Is that recuperation complete? Is it reversible? Maybe writing can be the writer’s dance with luxury, turning it, and being turned by it.

There is also the writing done out of necessity. I can pay the rent because I can write. Then there is the writing one does that is free, that comes from enjoying some minor surplus of life. What kind of luxury do I want for this writing? I’m torn. I fantasize about writing that’s a commercial success, but I’ve never been any good at that. My writing always ends up compromised, somewhere between freedom and necessity. Maybe it’s a place of negotiation between rival desires for kinds of luxury.

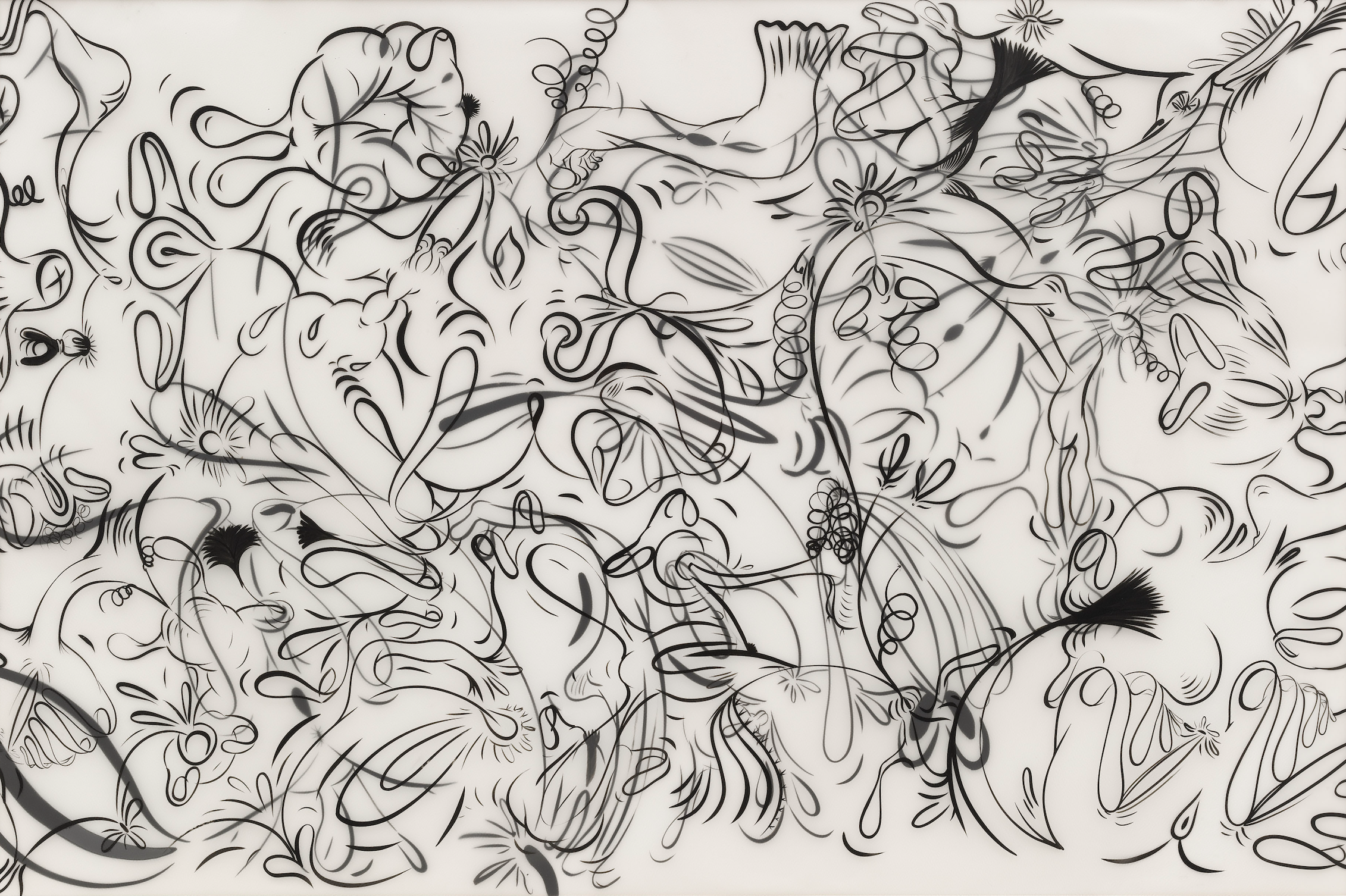

My guide to this dilemma has always been the writing of Georges Bataille, and not least because of how excessive it was. As he writes in The Accursed Share: ‘it is not necessity but its contrary, luxury, that presents living matter and mankind with their fundamental problems.’2 Luxury for Bataille is the condition of all life, as it draws energy, directly or indirectly, from the sun, using it to develop, grow, expand, proliferate. Everything over and above mere survival is luxury. ‘In the general effervescence of life, the tiger is a point of extreme incandescence. And this incandescence did in fact burn first in the remote depths of the sky, in the sun’s consumption.’3 Life is the unreturnable gift of the energy of sunlight folded into teeming forms and foaming flourishes which blaze across the eons.

Share article